By elocal magazine

By elocal magazine

The History of Taranaki (1878) by Benjamin Wells stands as a seminal colonial-era account of New Zealand’s formative conflicts between European settlers and the indigenous Maori tribes. It offers vivid and often harrowing eyewitness accounts of tribal customs, warfare, and particularly the practice of cannibalism. These documented observations invite a sobering historical reflection on the social structure, values, and warfare norms of the Maori during the early 19th century. Rather than portraying a caricatured form of savagery, this essay seeks to contextualize Maori violence and ritual within both local and global paradigms of the time.

Eyewitness Accounts of Cannibalism and Tribal Brutality

The most disturbing features of Wells’ account are his detailed descriptions of the treatment of captives and the ritualistic consumption of human flesh. He recalls atrocities during intertribal warfare and against European settlers. One passage describes an incident following an attack on settlers in Wairau:

“After the massacre the heads of Captain Wakefield and the other principal victims were cooked and eaten by the victors. The flesh of Europeans was in no way spared, and it was related with satisfaction that human flesh had been devoured by hundreds of savages at the great war feast.”

Another particularly gruesome account emerges during the description of war customs among Waikato and Taranaki tribes:

“The warriors, flushed with victory, piled the heads of their enemies in heaps and danced around them with fiendish delight. At night the ovens were heated, and before morning the bodies of the slain were eaten by their conquerors.”

Wells is careful to underscore that such actions were not merely acts of desperation, but culturally sanctioned practices meant to degrade the enemy, reinforce tribal dominance, and even invoke supernatural power through the act of consuming a foe.

The Martial Culture of the Maori

The Maori of the 19th century operated under a system of tribal law centered on mana (prestige, authority) and utu (reciprocal justice or revenge). Warfare was not an exception but a constant within this cultural framework, often driven by ancestral obligation, retribution, or competition for land and slaves.

Wells notes that:

“War with the Maori was not simply political—it was a spiritual duty, with blood debts inherited by the next generation. To them, peace without vengeance was dishonor.”

Slavery, mutilation, and ritual killing were common, and even Christian missionaries, while able to convert individuals, were often powerless to stem the entrenched cycles of violence between iwi (tribes). Wells recounts that:

“Even the missionaries, whose influence was growing, lamented that their teachings were set aside during warfare. Some converts returned from battle with flesh hanging from their belts, to the horror of their teachers.”

Global Context: Was Maori Violence Exceptional?

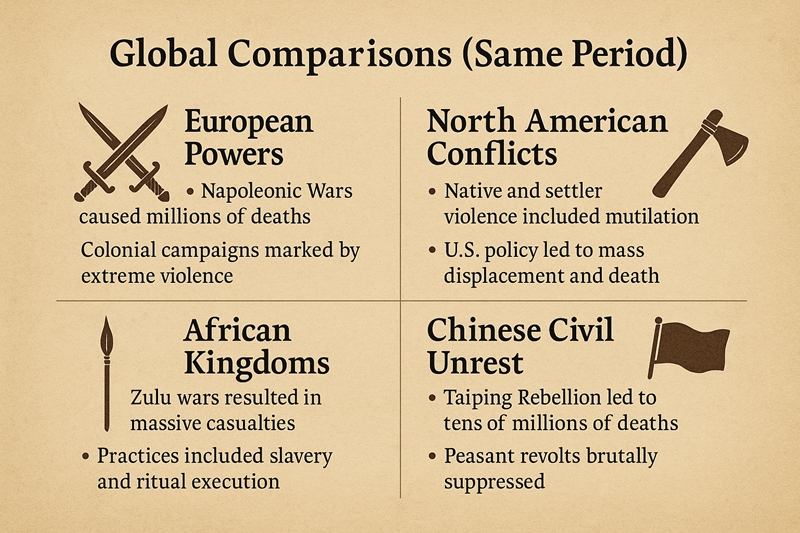

While Wells’ account is undeniably graphic, it is crucial to situate Maori practices within a global framework of the early 19th century. In Central Africa during this period, the Dahomey Kingdom engaged in large-scale ritual executions and slave raids. In North America, the Comanche and Apache tribes practiced brutal raids, torture, and scalping. In Europe, the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) saw mass conscriptions, state-sanctioned slaughter, and prisoner starvation. Even in the so-called "civilized" world, colonial retribution, forced labor, and mass displacements were the norm.

What distinguished the Maori was not the presence of violence, but the ceremonial nature of it. Cannibalism among Maori was not done for sustenance but as a cultural expression of conquest, humiliation, and spiritual warfare.

Conclusion: Context Over Comparison

Benjamin Wells’ History of Taranaki reveals a Maori world steeped in cycles of tribal vengeance, ritualized violence, and complex social laws. By quoting extensively from this firsthand colonial record, we see a people who lived within a world where brutality served both practical and spiritual functions.

To declare the Maori “more bloodthirsty” than other peoples is reductive and ignores global parallels. Rather, their behaviors reflected a pre-modern culture with its own logic, shaped by isolation, competition, and spiritual belief. When compared globally, Maori violence was not unique in intensity, but in its spiritual and ritualistic framing.

What Wells has given us is not merely a condemnation, but a stark reminder that the line between civilization and savagery is often drawn by the victor. His eyewitness testimony serves as a window—not only into the dark chapters of New Zealand’s past—but also into the universal human propensity for violence when law is local and honor is tribal.