By Independent News Roundup

By Independent News Roundup

You see it in the distance as you enter the sprawling complex of monuments and carefully manicured open space that comprises the half-million square foot expanse that is the Khatyn memorial to the victims of the Nazi genocide in Belarus—a black figure standing at the termination point of a pathway made of concrete slabs.

As you draw closer the form of the object becomes discernable—an man, his body battered and his clothing torn, cradling the body of a boy in his arms, his face a mask of unspeakable anguish.

Designed by sculptor Sergei Selikhanov, the statue depicts Yuzif Kaminsky, the only adult villager who survived the Nazi massacre in the Belorussian village of Khatyn on March 22, 1943, cradling the corpse of his dead son, Adam. Kaminskiy’s grief is meant to be representative of all the suffering inflicted on the Belorussian people by the German Nazis and their proxies.

Sergey Selikhanov was no ordinary sculptor. Born in 1917 in the city of Petrograd later renamed Leningrad, and today known as Saint Petersburgh, the same name it bore when it was first built by Peter the Great in the later 17th century), Sergey studied the fine arts, graduating in 1937 from the Vitebsk Art College. During the Great Patriotic War, Sergei served in the Red Army. He fought in the horrible battles outside Moscow and Rzhev, on the Kalinin and Voronezh fronts, and at the Kursk Bulge. He helped force the crossing of the Dnieper River, fought in Silesia and ended the war helping liberate Prague. He was awarded the Order of the Red Star, the Order of the Patriotic War of the 1st and 2nd degrees, the Badge of Honor, and the Medal “For Courage”.

Sergei knew the reality of war, and the face of suffering. And when called upon to design a statue for the Khatyn Memorial, he opted not to produce something from the school of socialist realism that defined most Soviet-era war memorials, but rather something more ragged, rough, that captured the raw emotion of a man who had watched an entire village be burned to death, including his family, and to find his son—his legacy, his future—amongst the slain.

The name of the statue Sergei produced was “The Unbowed Man.”

But for those who know, it is the statue of Yusik Kaminsky and his son, Adam.

The Khatyn Memorial is built on the land where the village bearing the same name once stood. On the morning of March 22, 1943, soldiers from the 118th Police Battalion and the SS-Sonderbattalion, led by Oskar Dirlewanger. The 118th Police Battalion was stood up in Kiev in 1942. Commanded by German officers, including Erich Korner and Hans Woelke, a famed German athlete who won a gold medal in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, the rank and file of the 118th Battalion was drawn from western Ukrainian nationalists who were members of the faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) led by Stepan Bandera. The Banderists were used by the Germans to carry out the most brutal repressions of the Russian and Belorussian people, actions that fit well with their ideology, founded as it was on the murderous advancement of Western Ukraine over all other regional peoples.

Dirlewanger’s SS-Sonderbattalion was created specifically for the purpose of implementing the policies associated with “Plan Ost”, the systemic annihilation of the non-Germanic population of the Soviet territory, including Belorussia, that was occupied by Nazi forces. Dirlewanger recruited rapists, murdered and psychopaths selected for their unquestioning willingness to engage in the systematic slaughter of targeted populations. Under Plan Ost, fully 75% of Belorussians were considered by the Germans as “unfit” for “Germanization” and targeted for liquidation.

According to Adolf Heusinger, a senior German General in the Operations Department of the German Army High Command, responsible for conceiving and implementing military operations against the Soviet Union, “The treatment of the civilian population and the methods of anti-partisan warfare in operational areas presented the highest political and military leaders with a welcome opportunity to carry out their plans, namely the systemic extermination of Slavism and Jewry.”

(Despite his direct knowledge and active role in the implementation of Plan Ost, Heusinger escaped prosecution after the end of the Second World War, and in 1955 returned to military service as a general officer in the new German Bundeswehr, eventually serving as the Inspector General of the Bundeswehr and the Chairman of the NATO Military Committee.)

Between the Banderist extremists and the psychopaths of the Dirlewanger SS-Sonderbattalion, the population of Khatyn never stood a chance.

The 22nd of March 1943 marked the Spring Equinox, a time when the sun is directly over the equator and day and night are of equal length. In Belorussia, the days leading up to the equinox are known as Maslenitsa, or “Butter Week”, a time of feasting and merrymaking before the start of Lent. In the homes of the village of Khatyn, wives and mothers were up early, preparing the dough for the various breads, cookies and cakes they would bake to celebrate this event. The children of the village either remained in their beds, or were scampering about, excited for the holiday to come.

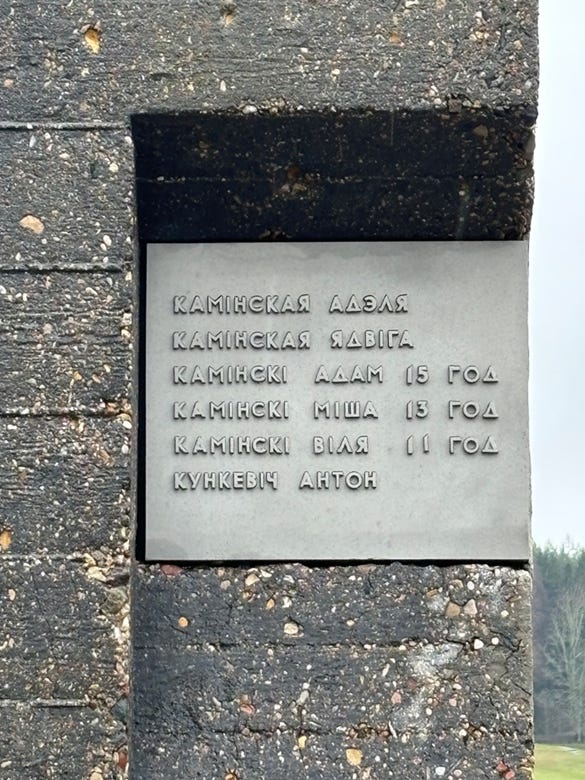

In the Kaminsky home, Yuzif sat around a table while his wife and Mother conducted the preparations for baking. Yuzif was joined by Anton Kunkevitch, who lived in a neighboring village and who had come to Khatyn to talk to Yuzif, who worked as a blacksmith, about helping craft several items he needed for his work. His three sons—Adam, Misha and Vilya—sat nearby, listening as the men talked.

Several kilometers away, the fate of Yuzif and his family, together with the rest of the occupants of Khatyn, was decided by others. Two companies of Belorussian partisans from the “Avenger” brigade positioned themselves along the road connecting Pleshchenitsy and Lahoisk. The partisans had cut the telephone wires, and looking to ambush any German vehicles that might arrive to conduct repairs.

Around noon on March 22, they got their wish. A small convoy consisting of three vehicles—an armored car and two trucks—approached the partisan positions. In the armored car was none other than Hans Woelke, the commander of the 1st Company of the 118th Police Battalion. Wolke was killed by the partisan fire, along with three of his Ukrainian auxiliaries. The partisans then fled from their ambush toward Khatyn.

Korner, the commander of the 118th Battalion, was incensed when he heard about Woelke’s death. Informed that the tracks of the partisans, which were visible in the snow that still lay on the ground, led to Khatyn, Korner ordered the 1st Company, together with reinforcements from the Dirlewanger SS-Sonderbattalion, to exterminate the village and all its occupants.

By the time the Germans had assembled the punitive force, the partisans had fled from the vicinity of Khatyn. Only a single female partisan was discovered in the forests outside Khatyn. She was executed on the spot.

According to the report of the partisans, “[Khatyn] was destroyed and all its inhabitants burned in the barn. In total 140 people were burned, among them seventy children between the ages of 1 and 14.”

Eight-year-old Viktor Andreevich Zhelobkovich was one of three survivors to emerge from the barn. In 1986, he provided this account of that horrible day:

That day before dinner my father and I went to the barn, to prepare hay for the cow. Suddenly we heard gunshots. We ran into the house, told all the people ... to hide in the basement. After some time the members of the punitive squad broke through the door to the basement and ordered us all out on the street. As we got out we saw that they were chasing people out of the other houses as well. They brought us to the barn, which stood a little bit outside the village.

I saw half-dressed and barefoot children. The Germans did not allow anybody to get dressed. The barn was 10 by 12 meters. The people calmed each other, told themselves ‘They are just trying to scare us and will let us go.’

We sat for about an hour. When someone climbed up under the ceiling to see what was going on, the punitive battalion noticed it and opened fire. The bullet passed me by.

Through the cracks I could see how they gathered hay and were pouring gasoline. People went out of their minds from fear, realizing that they were to be burned.”

My mother and I stood right by the locked barn doors, and I could see between the planks of the barn wall how they piled up hay against the wall, which they then set on fire. When the burning roof caved in the people and people’s clothes caught on fire, everybody threw themselves against the doors, which broke open.

The punitive squad stood around the barn and opened fire on the people, who were

running in all directions. We made it five or six meters from the doors of the barn,

then my mom pushed me to the ground, and we both lay there. I wanted to get up,

but she pressed my head down: “Don’t move, son, lie still.”

Something hit me hard in my arm. I was bleeding. I told my mom, but she didn’t answer—she was already dead.

How long I was lying there, I don’t know. Everything around me was burning,

even my mother’s clothes had begun to glow. Afterwards I realized that the punitive

squad had left and the shooting had ended, but still I waited awhile before I got up.

The barn had burned down, burned corpses lay all around. Someone moaned: “drink… ”

I ran, brought water, but to no avail, in front of my eyes the Khatyn villagers died one

after another. Terrible, painful deaths…

Yusif Kaminsky and his family, together with Anton Kunkevitch, were likewise herded into the barn. When the barn roof collapsed, Yusif and a number of other villagers were pressed into the door of the barn, which then burst open. Yusif stumbled forward, his clothes on fire. The Germans and their Ukrainian proxies opened fire on Yusif and the others. Yusif was hit in the leg and fell to the ground, unconscious. The others were killed. Yusif’s wounds and his burned body and smoldering clothes led the Germans and Ukrainians to believe he was dead.

Yusif regained consciousness after the Nazis had left. He searched the still smoldering bodies of his fellow villagers that surrounded him, looking for his family. Finally, he came upon the body of his 15-year-old son, Adam. Badly burned and shot in the stomach, Adam was still alive when Yusif found him. The father picked up his son and started to carry him to safety, but the boy died in his arms.

Yusif stumbled through the forest before reaching the neighboring village of Mokred. “I saw how the entire village was burned”, he said to the shocked villagers. The next day they and villagers from other surrounding villages made their way to Khatyn.

The village and its occupants were no more.

Yusif Kaminsky survived the war, and lived to see the memorial to Khatyn constructed, together with the statue of him carrying the body of his son. Kaminsky retired to a neighboring village some seven kilometers away. But for a decade after the memorial was built, Kaminsky would make the walk to the memorial, where he would stand by the ruins of his former home, in the shadow of the statue marking the most horrific moment of his life and share his thoughts and memories with visitors. “I owe it to the memory of my family,” he explained.

Yusif Kaminsky passed away in 1979.

Some 627 Belorussian villages were subjected to the “Khatyn treatment” by the Nazis, their entire populations herded into barns and burned to death. In total, more than 3.1 million Belarussians were killed by the Nazis—one in every three of its citizens. More than 12,000 villages were destroyed. Many of the perpetrators of this crime, including members of the 118th Polic Battalion, escaped justice by taking refuge in Canada, whose Ukrainian diaspora is marked by its pro-Bandera ideology. And today many Ukrainian soldiers proudly wear patches depicting the crossed stick grenade emblem of the Dirlewanger SS-Sonderbattalion.

If there was ever a justification for a memorial such as the one that exists in Khatyn, it is this disgusting refusal by the West to condemn the criminal ideology of those who today openly resurrect the murderous legacy of Nazi Germany’s genocide of the Belarussian people.

Stare long and hard at this statue.

Look at the slain body of his son.

Examine the pain and grief etched into the face of this man.

Say his name:

Yusif Kaminsky.

And never forget the crimes man can commit against his fellow man.

I want to give special thanks to my guide, Anna Papko, who brought the horrible memories of Khatyn to life for me. She has an unenviable job which she conducts with grace and humanity. She views it as necessary work.

She is right.

I am currently travelling in Russia, conducting interviews of prominent Russians in order to help capture the Russian reality and bring it to an American audience. This article was motivated by a visit to the Khatyn Memorial on November 12, 2025. If you want to see more articles like this, please subscribe. And if you want to help make possible more trips such as this, please donate.