By Democracy Action

By Democracy Action

This decision follows the first Court of Appeal interpretation of the Act, which involves a 40km stretch of coastline near Opotiki in the Bay of Plenty. In this case, ‘tikanga’ principles were given precedence over the common law test of exclusive use and occupation set out in the Act. Additionally, the Court accepted the concept of ‘shared exclusivity’. The dissenting judge in the majority ruling of that case noted that the Court of Appeal findings would make it “very much easier” for Maori to obtain customary rights. This prediction has proven true, as evidenced by the outcome of the case involving iwi and hapu claims to the Wairarapa coast.

The then Prime Minister John Key assured the public that only a “relatively small” amount New Zealand’s coast would end up going into customary title, and that most New Zealanders would notice no change.

In 2011, the Marine and Coastal (Takutai Moana) Area Act was passed by John Key’s National Government in collaboration with the Maori Party. This law repealed Crown ownership of the common marine and coastal area. Instead of the country’s foreshore and seabed being vested in the Crown on behalf of all New Zealanders, it became ‘public domain,’ thereby allowing Maori to seek customary title over the area.

The then Prime Minister John Key assured the public that only a “relatively small” amount New Zealand’s coast would end up going into customary title, and that most New Zealanders would notice no change.

However, this promise is proving to be false.

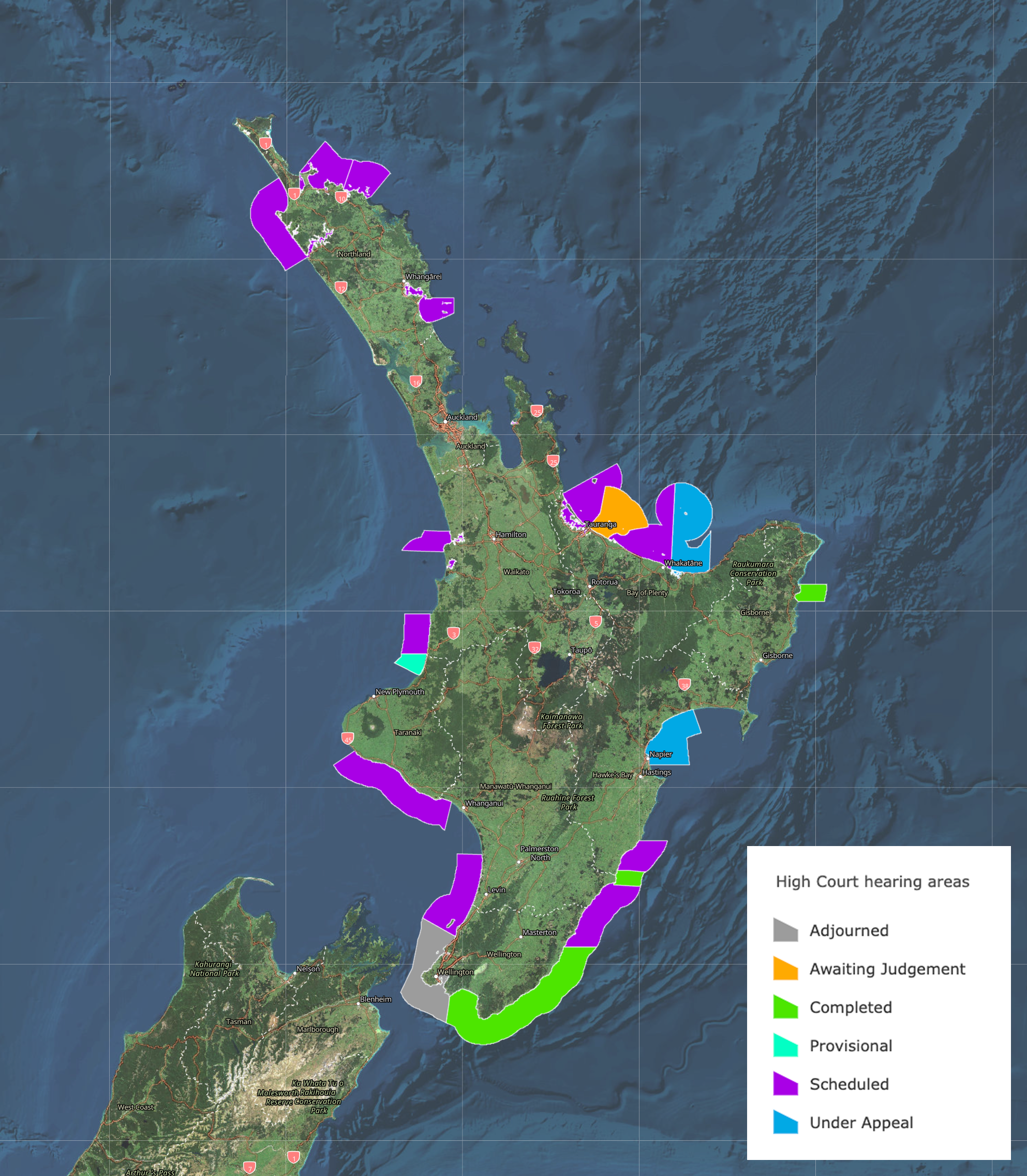

All New Zealand’s coastline is subject to claims.

There are still just under two hundred applications for the recognition of customary rights to be heard by the Courts. Additionally, around 385 applicants have chosen to seek the recognition of customary interests in the foreshore and seabed in direct negotiations with the Crown.

Currently, applications for the recognition of customary rights relating to the northern portion of the Wairarapa coast are being heard in the Wellington High Court.

At the same time, fifteen Maori groups have applications currently being heard in the High Court for the Whangarei Harbour.

Other areas where successful claimants have been granted customary rights in the common marine and coastal area include a 16km long stretch in Hawkes Bay; a section stretching from just south of Wairoa to south of Napier Harbour; Tauranga Harbour’s easternmost arm; and around two islands southwest of Stewart Island.

The High Court received a total of 202 claims that cover most of the coastline of New Zealand - from the mean high-water springs to the 12 nautical mile limit of the territorial sea. This map shows the status of the cases that are actively making their way through the courts as of 9 May 2024.

Rights provided under the legislation

The Marine and Coastal Area Act creates three new types of legal interest, rights that are only available to Maori. They are:

Customary Marine Title

A Customary Marine Title is a comprehensive right that includes elements of ownership, although with certain conditions attached. The legislation ensures public access to the common marine and coastal area, as well as protection of navigation and fishing rights.The group holding a Customary Marine Title cannot sell the area but may transfer the title to other individuals within the same iwi or hapu in accordance with Maori customary practices, (tikanga). However, a CMT group may delegate the rights to others conferred by a customary marine title order.

Once granted, the holders of a customary marine title have:

A CMT group has the authority to use, benefit from, and develop the designated CMT area, including the ability to derive commercial benefits. The group is exempt from coastal occupation charges related to the area under the Resource Management Act.

Protected Customary Rights

Protected Customary Rights are centred on the use and practice of certain activities. These rights are defined as those that have been continuously exercised since 1840 in accordance with tikanga, whether in their original form or with adaptations over time, and are not legally extinguished. These rights can include traditional activities like gathering hangi stones or launching waka in the common marine and coastal area.

Holders of a PCR are not required to obtain resource consent for customary activities, and local authorities cannot grant consent for activities that may negatively impact these rights. PCR holders can transfer or delegate their rights in line with tikanga. They can also gain commercial benefi ts such as selling sand or gravel.

When exercising a PCR, a rights group is not obligated to pay coastal occupation charges or royalties for sand and shingle under the Resource Management Act 1991.

Notably, an applicant group does not need to have a land interest in or adjacent to the specified area of the marine and coastal zone to establish protected customary rights.

The third entitlement is for all affected iwi, hapu or whanau to participate in consultation procedures in the common marine and coastal area. Affected iwi, hapu and whanau are those who practice kaitiakitanga, which is defined as exercise of guardianship or stewardship by the tangata whenua of an area in accordance with tikanga. The Director-General of Conservation must have regard to the views of such groups when making conservation decisions.

This extensive list of rights applied over large swathes of the New Zealand coastline makes a mockery of former Prime Minister John Key’s assurance that most people will notice no change. As a sign of things to come, iwi are demanding that the Port of Tauranga pay a mitigation fee of $75-100 million as a condition of their resource consent for expansion. Given the power conferred on iwi groups under MACA similar demands can be expected in the future unless the government makes changes to current legislation.

References